“It’s a shame when people can’t grasp the infinite—a failure not just of imagination but of simple vision.” —Jess Walter, “Beautiful Ruins”

“It’s a shame when people can’t grasp the infinite—a failure not just of imagination but of simple vision.” —Jess Walter, “Beautiful Ruins”

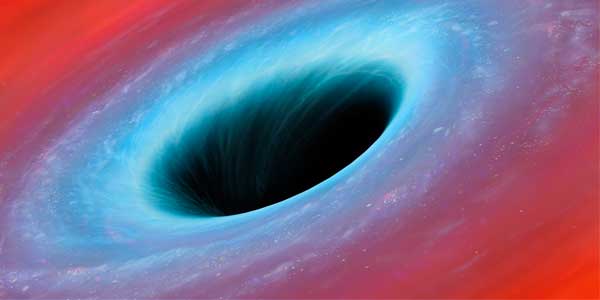

For too long in the business world, the “black hole” has gotten a bad rap.

Think about it. When something doesn’t get done, it’s said to have gone down a black hole. Haven’t heard from a colleague in a while? They’ve fallen into a black hole. A black hole swallows things up. That’s not good.

A little closer to home, marketing is often called the black hole of business. That’s the finger-pointing state of affairs when too much money is spent on tactics that simply do not generate results, says management consultants White Board Business. The Financial Times agrees. Its definition of a black hole: “A business activity or product on which large amounts of money are spent, but that does not produce any income or other useful result.”

Right.

Well, the agitator in me is pleased to inform you the ignominious black hole is about to become a new, international source of inspiration (click to tweet).

But first we need to go back 100 years. That’s when Albert Einstein applied his newly discovered theory of relativity to show that outer space, or even the space between you and the device you’re reading this on, reacts to the presence of matter by curving, expanding or contracting. In a fascinating piece in The New York Times last week, Lawrence M. Krauss, a theoretical physicist, wrote that each time we wave our hands around or move matter of any kind, gravitational waves are created and shoot through space like a rock thrown in a lake, causing oscillations between objects.

Last Thursday, in a triumph over mind-boggling odds, scientists proved those ripples exist by discovering a signal emanating from two massive black holes that collided and merged over a billion light years away. You probably recall from Physics class that one light-year is about 5.88 trillion miles. For those of you who are not fully-caffeinated allow me to repeat—these black holes are one billion times 5.88 trillion miles away from where you’re sitting.

To detect that signal—one so far away it almost defies comprehension—scientists built two gigantic detectors consisting of two tunnels, each about 2.5 miles in length and perpendicular to each other. Krauss writes: “(The experimenters) had to be able to measure a periodic difference in the length between the two tunnels by a distance of less than one ten-thousandth the size of a single proton.”

Please put down your coffee cup for this next bit: “It is equivalent to measuring the distance between the earth and the nearest star with an accuracy of the width of a human hair.”

You may have heard this story last week and thought what’s the big deal, how’s this going to change anyone’s life, Einstein was a smart guy and now a bunch of people proved it.

Well, yes, the jury’s out as to whether this work will eventually improve your wi-fi signal or help you sleep seven full hours. But I would argue, as Krauss did, that this kind of amazing human achievement, like a Picasso painting or a Mozart symphony—or creative work that lifts a client—is the kind of soaring endeavor that inspires awe, wonder, joy, and in so doing, confirms our relative place in the universe.

As communicators, those breakthrough moments are what we live for, what we dedicate our careers to, and what turns today’s burgeoning luminaries into tomorrow’s stars.

So, as those stars align, the time is right to set the record straight: Marketing is anything but the black hole of business—as exciting to many of us as space exploration itself. And it can yield tremendous results, especially when coupled with the breakthrough power of public relations.

“The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies—were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star-stuff.”—Carl Sagan