As a former journalist and now communications consultant, I dislike association with the term “spin” because it assumes that public relations is about deceit or propaganda. Like it or not, spin is a part of the partisan political world, especially during a hotly contested race for the White House. But when it comes to matters of public health, spin can quickly burn the credibility of a scientist. We saw this take place this weekend, with some important lessons for clients who live in the science world.

During a Saturday briefing led by President Trump’s personal physician, Dr. Sean Conley, Dr. Conley was upbeat about the President’s condition and worked very hard to avoid a headline that the President needed supplemental oxygen on Friday. Reporters asked several variations of the oxygen question and he danced around confirmation by saying, “He’s not on oxygen now,” and, “Thursday no oxygen, none at this moment, and yeah, yesterday with the team, while we were all here, he was not on oxygen.” All true, and conveniently, all avoiding the time Friday morning at the White House when Dr. Conley provided supplemental oxygen to the President.

That is textbook spinning—providing facts that build your case while purposely omitting facts that go against it. The doctor’s credibility was further compromised when a White House official spoke to reporters and suggested the President’s health picture was more serious than the doctor’s portrayal, that oxygen had been administered and that the timeline he presented was wrong. The next day, at Sunday’s briefing, Dr. Conley rationalized his evasion of the oxygen question by saying he “was trying to reflect the upbeat attitude of the team” and “didn’t want to give any information that might steer the course of illness in another direction and in doing so, came off like we were trying to hide something which wasn’t necessarily true.”

The problems with spinning in this serious situation are plentiful. Not only has Dr. Conley lost credibility for future briefings, but he made a somewhat routine procedure, administering oxygen, seem more serious and newsworthy than it was. It’s also fair to say that, unlike many political pros, he’s not a very good spinner.

Dr. Conley’s experience helps reaffirm the advice we give to our clients about their experts. Doctors, engineers, food scientists and other experts all can help a company tell positive stories and lend credibility as spokespeople during a crisis. But it’s important that they are prepared for those situations and not left on their own to decipher the codes of PR ethics. For media relations where expertise is required, remember:

- Be honest. Not only is this part of our PR industry code, but anything less than honesty will override whatever credibility you hoped to achieve with an expert.

- Be transparent, even when you choose NOT to say something. It’s okay to decide that certain information will be off limits. But be transparent about your reasons. “Here’s why we won’t be releasing that information” is much better than dodging and weaving as Dr. Conley did.

- Assume the full story will come out. While spinning may conceal a negative fact in the short term, the reality is that the story will eventually come out. Ideally, you can get the whole story out at first and get it over with. If you can’t, recognize that you will be judged later on how and why you held back certain information.

- Support your spokespeople. Most of your experts are not media experts. As communications professionals, we know how to run a live briefing, when to end it, when to cut off certain types of questions. Asking physicians to run a full briefing, as happened this weekend, is not the best use of their skills.

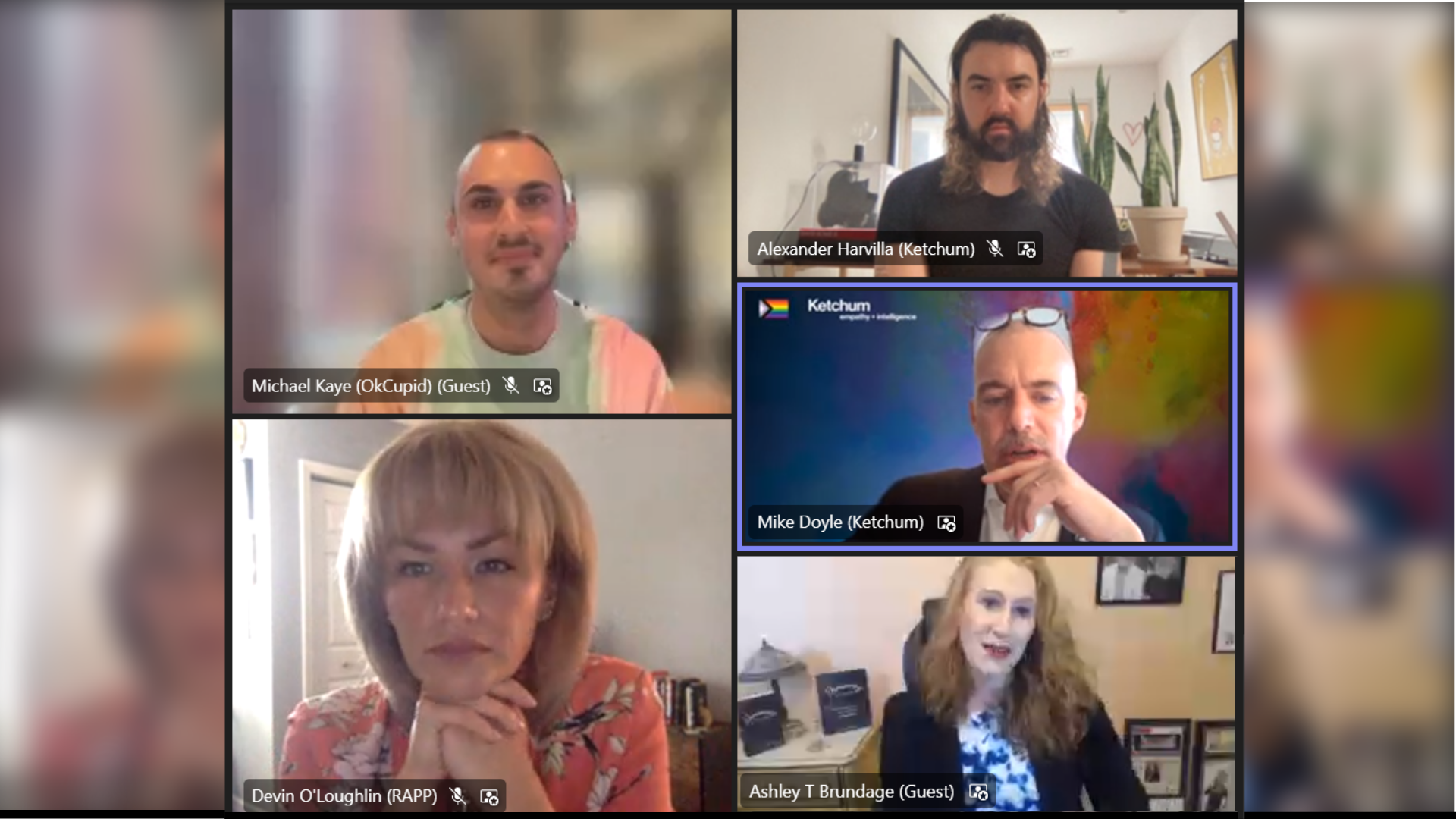

- Be prepared. A fast-moving issue is no time to determine whether experts are media-ready. Communications training, including issues prep, is vital for anyone you anticipate may need to speak for the company in a difficult situation. (And yes, we offer that here at Ketchum. Click here if you’d like to arrange to train your experts remotely during the pandemic.)

As the White House continues to manage information around the President’s illness, it will be interesting to see the spokesperson changes they choose to make, or are forced to make, following this incident. For corporate communicators it’s a good lesson: Spinning, sometimes, just makes you dizzy.